Guac or guacamole?

A reflection on how culture is erased through language

Every now and then, I have the chance to experience a bit of luxury . For some, brunch is a routine weekend ritual, but for me it remains an extraordinary occasion. Recently, some friends invited Andrea and me to a restaurant with a beautiful view of Dublin’s Docklands. It was only 10 in the morning, yet the place was already filling with locals and tourists eager to sample the city’s food culture.

I often feel a twinge of disappointment at brunch spots, since most of them serve more or less the same menu: eggs breakfast, pancakes, eggs Benedict, Turkish eggs, waffles. But this time I noticed an anomaly: “Mexican Breakfast.” Intrigued, I leaned in to read the description carefully.

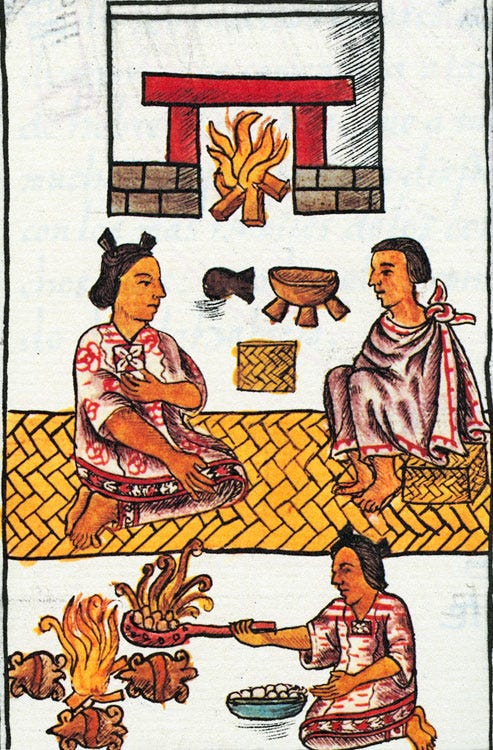

“The codices, manuscripts created by Indigenous peoples during the Spanish evangelization, allow us to trace the culinary everyday life of the Mexica. Among them appear materials such as the molcajete, which is popularly associated with the preparation of guacamole”

I read it two, three times, as though it had been written by someone careless or simply convinced no one would notice the typos. I showed it to Andrea and to my friends, wondering: was this menu created before ChatGPT? Perhaps it will be a long time before anyone bothers to reprint it with the names spelled correctly.

And then suddenly, as if swept by a twenty-meter wave, the words seemed to vanish and be replaced by others more in line with social norms. This was no longer just a careless mistake, but a linguistic mutilation. Not a minor scratch, but a kind of cultural amputation: Guac. Overnight, guacamole disappeared from the vocabulary of diners. Restaurants and bars adapted or risked fading away. The word had been put through a kind of cosmetic surgery: too long, too hard for an American tongue to pronounce, too far removed from the aesthetics of cool.

U.S. chains were the first to abbreviate it as guac. Practical, easy, and above all functional, it lets customers highlight on their taco or burrito order that they want “extra guac” for two dollars more. Born in the United States, the phenomenon spread quickly to Europe and Ireland, where it has also taken hold.

More guac: the larger and flashier, the cooler you’ll look!

But guacamole is a word with deep history. It comes from the Náhuatl āhuacamōlli: āhuacatl means avocado and mōlli means sauce or mixture. Archaeological evidence shows it has been consumed for more than 10,000 years. In Mesoamerica, cultures domesticated different varieties of avocado and used them not only as food, but also in rituals, offerings, and trade alongside cacao, maize, squash, and other staples of Mexica life. With colonization, avocado, like so many other fruits, metals, and food, was carried to Spain and then to the rest of Europe.

By the 1980s and 1990s, chains like Taco Bell and Chipotle had popularized the abbreviation guac, turning it into a marketing success. Little by little it seeped into foodie jargon and into the vocabulary of critics and consumers alike. In Ireland, chains such as Boojum or Tolteca helped spread the trend, while more specialized restaurants, consciously or not, have resisted by keeping the full word on their menus: guacamole.

Some people even refuse to eat avocado altogether for ethical reasons: land overexploitation, cartel control in Mexico, the abuse of agricultural workers. But by that logic, maize would also need to be questioned. In Ireland, the most accessible corn flour comes from Maseca, a monopolistic company whose practices have long degraded the land. And the avocados we eat here typically come from Spain, South Africa, or Indonesia, where exploitation and environmental damage are no less intense.

From a Lévi-Straussian perspective of the signifier, guacamole evokes a complex cultural meaning, tied to tradition and ritual. Guac, in contrast, signals an easy, digestible, trendy consumption, reshaped so that dominant cultures can absorb it into their own modern myth. At this point, Bolívar Echeverría is especially relevant: he argued that capitalist modernity operates through whiteness, a cultural mandate compelling colonized societies to reproduce European symbolic traits as the price of belonging to modernity. The shift from guacamole to guac is not innocent, it inscribes the food into the logic of whiteness, where the original must be pared down and repackaged in order to circulate as a global commodity.

“Whiteness is not simply a racial condition, but the normativity of a way of life that imposes European values as universal, marginalizing or erasing other cultural codes.” Bolivar Echeverría

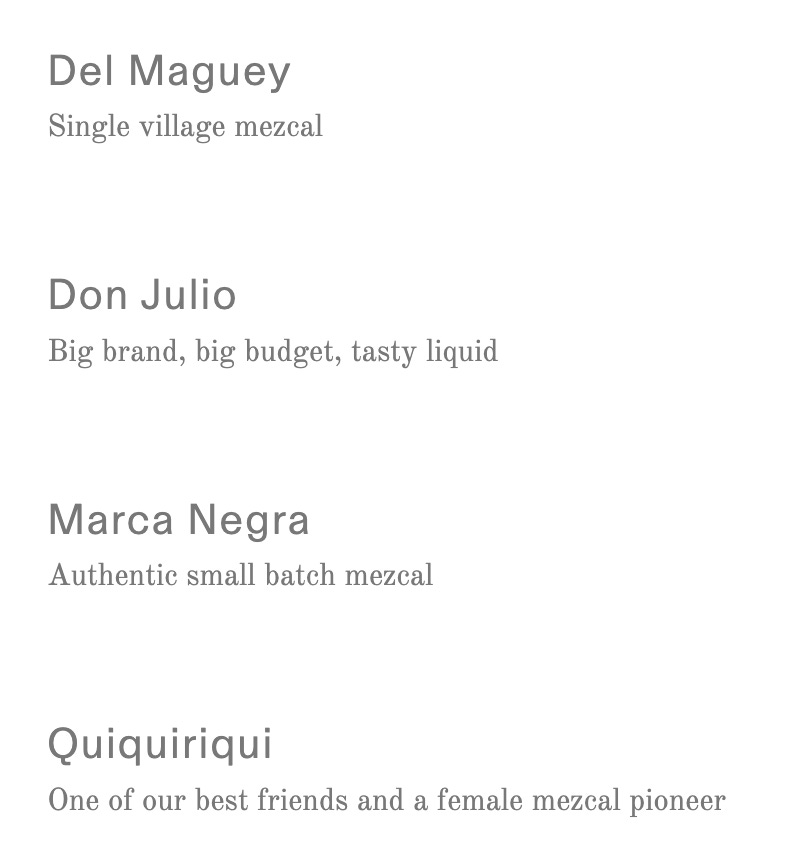

And this phenomenon is not limited to global fast-food chains. Even independent bars and restaurants reproduce—often unconsciously—the same practices, muting or decontextualizing language in order to align with an aspirational lifestyle. This was clear to me in a recently award-winning Dublin cocktail bar, celebrated for its design and luxury appeal to connoisseurs and clients eager for curated experiences. Yet in its spirits menu, tequila and mezcal were listed together under the same category, as if they were interchangeable.

“An excerpt from the menu in the Agave section. Spoiler alert: there are at least 150 varieties of agave in Mexico.”

Take Quiquiriqui mezcal, described by this bar as “One of our best friends and a female mezcal pioneer.” But what does this actually mean? What kind of agave is it? Where is it produced? Is it artisanal mezcal, or ancestral mezcal? Are there fair agreements with the mezcaleros? Who owns the land? None of these questions seem to matter, because what counts is not the context but the perception of authentic mezcal, mezcal cool. Paradoxically, this brand distributes only in the UK, Europe, the United States, Hong Kong, Singapore, and China. In Mexico, where it is made, it is not even available.

Something similar happens with Del Maguey mezcal, which is also sold at this bar. The brand, acquired by the French conglomerate Pernod Ricard, boasts a fair-trade ethos. Yet it is widely known that mezcaleros are paid between 7 and 15 pesos per liter, a minimal sum compared to the drink’s international market value.

Both cases—the rise of guac and the fetish of mezcal cool—reveal the same logic of capitalist modernity: to absorb, simplify, and aestheticize the other in order to turn it into commodity. It is a process that makes products visible but renders producers invisible; that globalizes consumption while localizing precarity. As Bolívar Echeverría once wrote: “Whiteness is the cultural mandate compelling colonized societies to reproduce the symbolic traits of European life as the condition for belonging to modernity.” And yet, in practice, it is not these critical voices that define what “Mexican” food or drink means abroad. It is the marketplace—the chains, the bars, the menus—that narrate Mexico for the world, smoothing out complexity into a digestible fantasy. Minority discourses that insist on naming guacamole as guacamole, or on recognizing the agave and the complexity and the mysticism of the mezcales, are fragile and difficult to sustain against the weight of commercial storytelling.

To soothe the frustration these reflections bring, I’ll prepare some guacamole, topped with chapulines (spicy grasshoppers) my mother secretly brought from Mexico.

This blog should be bigger